THE PRE 6 APRIL 2025 RULES

Individuals

So, what are these favourable rules that are being scrapped?

Firstly, various changes have taken place to the non-dom / remittance basis rules over the years. Each sortie by the legislator taking its toll on the attractiveness of these rules.

As such, I will look at some of the history which, I aver, it might be useful to know. So, let’s see what we can Golden Retrieve from the memory banks.

Income tax and Capital Gains Tax (”CGT”)

The remittance basis simply provides the non-dom taxpayer with the privilege of leaving his or her foreign income and gains (“FIG”) overseas without any tax being paid. If he or she leaves it overseas then there is no tax to pay. However, if he or she brings, enjoys or uses the funds in the UK then they will suffer tax to the extent that they do so.

If it is foreign income that is ‘remitted’ then it will suffer UK income tax. If it is a foreign gain that is remitted then it will suffer CGT. When the funds remitted were ‘mixed’ then special rules would apply.

In order to use the remittance basis, one must make an election and potentially pay a fee to use it1. The amount payable depends on how many years one has been resident in the UK:

- less than 7/9 tax years: the remittance basis is ‘free of charge’;

- between 7/9 tax years and 12/14 tax years: the remittance basis charge is £30k

- if one has been resident in the UK for 12/14 or more tax years and 17/20 tax years then one must pay 60k.

Prior to 2017, there was another tier of 17/20 tax years at which point the Remittance Basis Charge was £90k. However, this was scrapped when that years Finance Act created a long-stop date of being able to use the remittance basis of 15/20 tax years after which the ability to use the remittance basis was pulled (this was known as being deemed domiciled for income tax and CGT purposes).

A taxpayer had flexibility to choose whether to pay the Remittance Basis Charge in one year and not another. It would simply be a ‘cost v benefit’ calculation for a particular tax year.

Inheritance Tax (“IHT”)

Under pre 6 April 2025 rules, IHT primarily looked one’s domicile position rather than residence.

The position is that if one is domiciled in the UK then you pay UK IHT on worldwide assets. Whether that person is non-resident at the point of death is largely unimportant (unless also franked by valid claims to be non-UK domiciled).

A non-domiciled (and non-deemed) individual is subject to IHT on UK assets only.

Prior to 2017, a non-dom who had been resident in the UK for 17 out of 20 tax years would become ‘deemed domiciled’ for IHT purposes only. However, with the concept of ‘deemed domiciled’ being introduced for income tax and CGT as well, the threshold became 15/20 tax years across the board.

The rules for trusts

The concept of protected trusts was introduced in 2017.

Let us first remind ourselves of the framework that preceded that one.

The Pre-2017 position

The basic position before 2017 was that a non-UK trust (other than in respect of UK residential property from April 2015) did not pay UK CGT regardless of where the asset was located. This is based on the fundamental jurisdictional basis of UK CGT.

However, such a simple rule – which would be open to significant abuse if existed in isolation – was bolstered by a plethora of anti-avoidance rules2.

Prior to 2017, those anti-avoidance rules:

- looked to attach the gains of the trust to a UK settlor under certain circumstances; or

- alternatively, looked to attach the gains of the trust to a UK beneficiary.

Under those rules, where a settlor retained an interest (for ease, let’s say they may still benefit from the trust property) under a non-UK trust then the tax position depended on the settlor’s domicile position:

- a UK domiciled settlor: taxed on the trust gains as they arise (under TCGA1992, s86;

- a non-dom settlor was not

Where the trust was not settlor interested then the anti-avoidance code switched its beady eyes to the beneficiaries of the trust.

Specifically, it looked to see whether there was a link between the beneficiary and the UK:

- If the beneficiary was UK resident and domiciled

then capital payments (or benefits) he or she received were matched with any trust gains and the beneficiary pays tax;

- If the beneficiary was non-dom

then, he or she was only taxable (in respect of any capital payments or benefits matched with trust gains) on the remittance basis;

- If the beneficiary was non-dom and non-resident

then the provisions (TCGA 1992, s87) were unlikely to impose a charge (subject to other anti-avoidance rules).

IHT for trusts

Under the pre-April 2025 rules, trusts established by non-domiciled individuals would benefit from the attractive excluded property regime to the extent that property in the trust was of a non-UK situs.

Broadly, such property is outside of the scope of UK IHT status to the extent that the trustees hold non-UK assets. In addition, this includes trust property being outside of the Relevant Property Trust regime (eg 10 year / exit charge) for trusts.

As to whether trust property was excluded property the domicile status of the settlor was tested only at the time the trust was established. So, if the settlor subsequently became deemed domiciled for IHT purposes, this did not matter. The trust property remained excluded property and outside of any person’s estate and was no relevant property.

Finally, the Gift with Reservation of Benefit Rules (“GWROB”) were trumped by the excluded property rules. This meant that the settlor could retain an interest but the value of the assets would remain outside his or her estate.

B.I.N.G.O.

The position between April 2017 – 5 April 2025 & Protected trusts

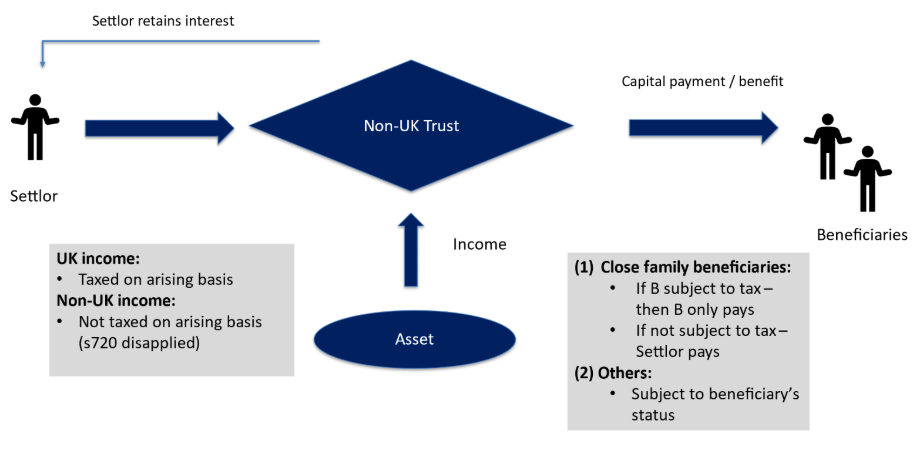

The basic position for trusts – whether considering income or capital gains - was no different to that which existed prior to 2017.

However, again, the complications came when it comes to the anti-avoidance provisions at work. As we have seen above, under the previous rules, relief was given where non-doms were the settlors of such trusts and / or where such people received benefits from said trust.

The rules between 2017-2025 had some additional problems to grapple. This was because it was in 2017 that the concept of ‘deemed domicile’ was introduced for income tax and CGT purposes. In other words, a long stop date to the benefits a non-dom can obtain.

Of course, for those non-domiciled individuals who had set up trusts before they became deemed domiciled under the new rules, removing the reliefs described above from the trust anti-avoidance provisions would be a massive rug-pull.

This ‘protected trust’ relief applied to those who set up trusts whilst non-dom but who became ‘deemed-dom’ in years from 2017/18 onwards.

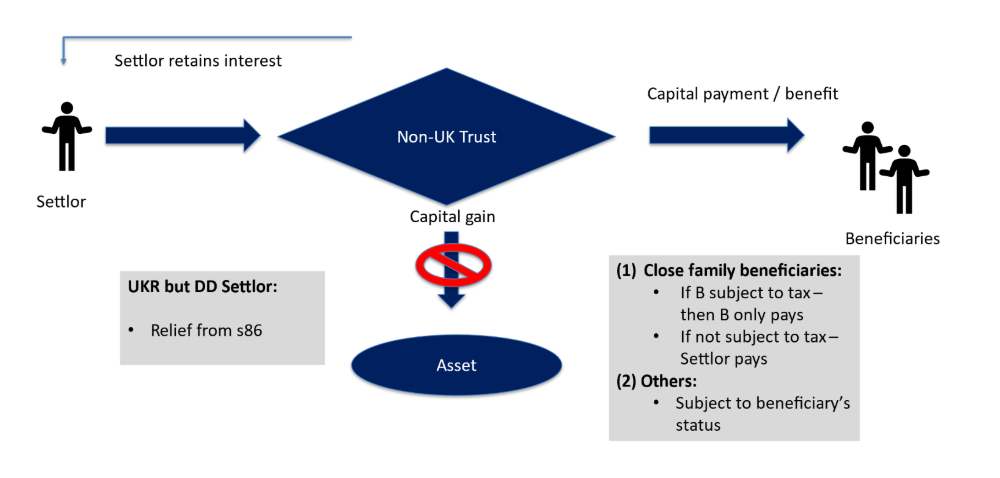

Under the CGT trust protections, s86 generally did not apply where a settlor became deemed domiciled under the new rules. This meant that whilst value is left within the trust

there will be a gross roll up of gains.

Instead, the tax position focused on capital payments or benefits actually paid out to beneficiaries.

The tax treatment depended on which category of person the payment or benefit is made to:

- Close family members (spouses, co-habitees, minor children, not grandchildren):

- Other persons

Where receipt is by a close family member then, if they were subject to tax on the receipt, then that was that. If not, for instance they were non-resident, then the Settlor was liable for tax.

If the receipt was by an ‘other person’ then the tax position was dependent on the recipient’s status. Of course, if it is the settlor then he will pay tax based on his own position.

Illustration – Protected trusts and CGT summary